Report Highlights Need for Additional Revenue Options

3/6/2012

The current top federal income tax rate is 35 percent. But what would the top rate have to be in order to raise enough federal revenues to cover spending? A recent paper from the Tax Policy Center (TPC) and the Pew Fiscal Analysis Initiative sets out to answer that question, but its answer is incomplete. To bring federal revenues up from their current historic lows, Congress needs to consider more revenue options than just raising individual income tax rates.

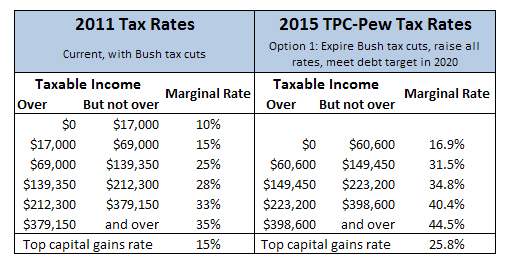

The TPC-Pew report looks at what level income tax rates would have to be in order to bring the debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP, a measure of the economy) ratio to 60 percent, a target used by some economists to measure fiscal sustainability. (Currently, federal revenues are at their lowest levels since the Truman era.) The report estimates the tax rates Congress would need to set to hit this deficit reduction goal, using three policy options: Option 1, raise all individual income tax rates, including those on capital gains and dividends; Option 2, raise the top three income tax rates without touching capital gains or dividends rates; and Option 3, raise just the top two income tax rates. With Congress debating the fate of the upper-income Bush tax cuts, this report gives policymakers a sense of the budgetary impact they could see from raising taxes on only the nation's wealthiest.

If all income tax rates were raised, as well as the capital gains and dividends rates, the TPC-Pew report estimates that individual tax rates would need to be moderately increased to hit the debt target. Assuming the expiration of all the Bush tax cuts, the current lowest tax rate would rise from 10 percent to 15 percent, and to reduce the debt, it would increase more – to 16.9 percent. On the other end of the income scale, those earning over $398,600 would see their rates increase from 35 percent to 44.5 percent, and the top capital gains rate would rise to 25.8 percent, up from its current modern low of 15 percent.

The study suggests that if the Bush tax cuts do not expire and only high-income tax rates are raised, taxes on all income over $146,450 would have to rise to at least 100 percent to meet the 60 percent debt-to-GDP ratio in 2020, an unrealistic proposal.

However, the target date for debt reduction is arbitrary, and there are other revenue options. For example, tax brackets could change. In 1991, the top tax rate covered all income over $135,000 (for married couples, in inflation-adjusted dollars), but today, it only covers income over about $380,000. This means that, today, $245,000 more of income is sheltered from the highest tax rates. Changing these brackets to subject more income to higher rates, which Congress has done many times in the past, would drastically change the shape of the individual income tax and help bring in more revenue.

Another option would be to tax capital gains as ordinary income, instead of giving it a preferential rate. Taxing such income just like wages could raise close to a trillion dollars over the next ten years.

A financial transactions tax is another alternative. This is a tiny tax placed on the trading of Wall Street financial instruments, including stocks, bonds, derivatives, futures, options, and credit default swaps. Many products are taxed at the point of sale, and taxing the sale of stocks and bonds would bring these transactions in line with other elements of the tax code. In fact, the United States had a financial speculation tax in place between 1914 and 1966, when the federal government levied a 0.02 percent tax ($2 on every $10,000 traded) on all sales or transfers of stock. If Congress enacted a financial speculation tax, the country could raise between $391 billion and $1.8 trillion over the next 10 years, depending on which financial products policymakers chose to tax and at what rates.

Finally, Congress could limit a wide variety of tax breaks, instead of only raising rates. Recently, President Obama has called for limiting itemized deductions for those earning over $250,000 a year. When filing a tax return, a household may subtract, or deduct, some expenses (including gifts to charity and mortgage interest) from the income on which they must pay taxes. These itemized deductions essentially shield a certain amount of income from taxation, thus lowering the taxes owed. Because tax rates are graduated, though, the more money you make and the higher your tax rate, the more beneficial itemized deductions become. Capping the amount of itemized deductions allowed for upper-income taxpayers would increase tax fairness, while bringing in as much as $584 billion over ten years.

[For more information on revenue choices, see OMB Watch's revenue project, We Have Choices.]

In addition to returning the top two or three rates to their pre-Bush tax cut levels, these other revenue options could do a great deal to bring federal revenues up from their current historic lows. Congress should examine all of the options on the table and choose those that increase the progressivity of our tax system and reduce debt over a reasonable time period.