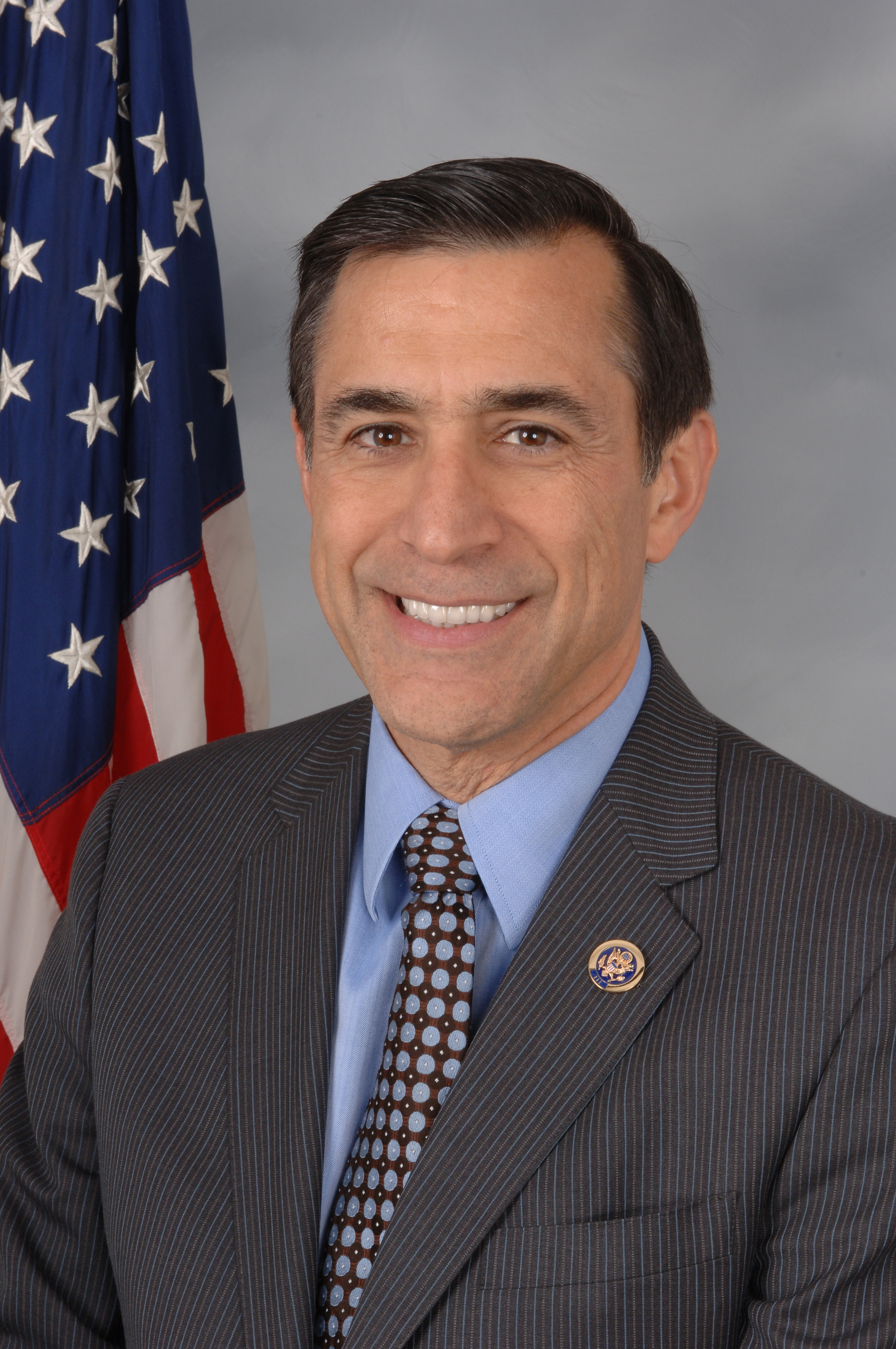

Commentary: Issa Releases New Spending Transparency Bill

6/14/2011

On June 13, House Oversight and Government Reform Committee Chair Darrell Issa (R-CA) introduced a bill to revamp federal spending transparency. The new bill, called the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act), would create a new board to oversee spending transparency, as well as implement full multi-tier recipient reporting. While the bill is a welcome effort to improve federal spending transparency, it still lacks some key details, contains a few worrisome provisions, and does not go far enough in broadening transparency in federal spending.

On June 13, House Oversight and Government Reform Committee Chair Darrell Issa (R-CA) introduced a bill to revamp federal spending transparency. The new bill, called the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act), would create a new board to oversee spending transparency, as well as implement full multi-tier recipient reporting. While the bill is a welcome effort to improve federal spending transparency, it still lacks some key details, contains a few worrisome provisions, and does not go far enough in broadening transparency in federal spending.

The most significant action in the DATA Act is the creation of a new independent agency, the Federal Accountability and Spending Transparency Board, or FAST Board. The Board would essentially be a reinvention of the current Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board, which oversees the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act's transparency provisions and investigates potential abuses. The new FAST Board would extend its powers to all of federal spending while also taking control of USAspending.gov from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Also on June 13, President Obama issued an executive order that creates a similar oversight board, called the Government Accountability and Transparency Board. In describing how the order will be implemented, Vice President Joe Biden noted that the administration has been working with Issa and other Republicans and Democrats in Congress to create the oversight board. Issa also stated that his FAST Board idea is being developed in collaboration with the administration.

Under the Issa bill, the Board would be led by a chairperson, who would be Senate-confirmed in a similar process to how the Comptroller General – the head of the Government Accountability Office (GAO) – is chosen. The Board itself is made up of a handful of agency inspectors general, deputy secretaries, and OMB officials. The DATA Act grants the Board subpoena power, as well as a limited ability to set federal data standards.

The FAST Board would then be charged with overhauling federal spending transparency procedures. Most notably, the DATA Act calls for recipient reporting to supplant the current system, the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA), which mostly relies on agency reporting (OMB Watch was involved in the creation of both FFATA and USAspending.gov). Similar to the Recovery Act model, under the DATA Act, all recipients of federal funds would be required to report on their use of the money. This is an important improvement over the current model.

The DATA Act also calls for the FAST Board to create common data elements and data standards to be used throughout all of the federal government's spending information systems. These improvements to financial reporting data could significantly enhance the ability of various federal data systems to communicate with each other, furthering data accessibility to the public and federal agency workers. To help ensure that recipient reports are accurate, the DATA Act also requires that agencies continue to report on their awards. These reports would be used to help verify recipient-reported data.

All of this information, the recipient reports and the agency-reported data, would be stored and displayed on a new website created by the FAST Board. Since the Board is independent, it could also serve as a "transparency portal," combining its spending data with other data sets it might find relevant.

However, what is most striking about the DATA Act is what is not in it. While the new legislation does improve federal spending in a number of ways, it still needs further refinement. The definition of "recipient" in the legislation is so vague that it is unclear if private entities (e.g., corporations) must report on their federal awards or if the DATA Act requires full, multi-tier reporting. And while the list of data points recipients must report is similar to both FFATA's and the Recovery Act's, it is missing some important points, such as place of performance and project status. Unfortunately, the new legislation also fails to require a new unique identifier for companies, a problem that has plagued federal data sets for years.

Similarly, it is strange that the DATA Act calls for agency-reported data, despite the fact that the bill is supposedly premised on the idea that agency-reported information is not high quality (an accompanying press release from the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee notes USAspending.gov data quality issues). Far better would be the inclusion of Treasury spending data, which is information on the actual cash outlays of the federal government. Treasury accounts are like the checkbook of the federal government: they are considered the gold standard for federal spending information. Information from these accounts would show exactly how much federal money was given to which entities. (This morning, June 14, during a hearing on the bill, Issa suggested that there may be a floor amendment mandating Treasury information, but as it is currently written, the bill does not do so.)

The DATA Act also does not include what is possibly the most obvious data check: having recipients report on their sub-awards. In the bill, as it is currently drafted, recipients only report on what they receive, not also what they give as sub-awards. If the recipient and subrecipient are reporting both what they received and what they gave out, the two reports can serve as checks on each other. Including such a requirement would substantially improve recipient report data quality, as well as cut down on waste, fraud, and abuse.

At the same time, the DATA Act doesn't require any performance information, either in the recipient reports or on the new website. One of the important lessons of the Recovery Act is that recipient reports are most useful when they include some kind performance metric. For instance, a housing project should note how many houses were built, or a road project should specify how many miles of roads were paved. Such information can help users understand if federal programs are meeting their performance goals, which should also be displayed on the new spending website. Linking spending and performance information on the same public website is the next important step in transparency, and the DATA Act does not take that step.

In addition to these issues is the FAST Board's exemption power. Under the DATA Act, the Board would be able to unilaterally exempt whole classes of recipients from the reporting requirement. While the Board would be required to publish aggregated data on "information that is exempt from recipient reporting ... but that is reported by an Executive agency," the Board would not be required to disclose why it exempted the recipients. Thus, not only would the public not know what information was left out of the recipient reports, they would not know why the information was exempted.

Strikingly, the DATA Act does not address a key area of government spending that has remained hidden – tax expenditures. Tax expenditures now account for about $1 trillion per year but largely go unreported. While it is challenging to make such information publicly accessible, the bill should at a minimum require the FAST Board to develop a plan for such disclosure.

Perhaps the most worrisome aspect of the DATA Act is that it also repeals FFATA, to date the most important spending transparency law ever passed. This action is especially problematic because the DATA Act has a sunset provision, which would require Congress to reauthorize the law in seven years. If Congress fails to act in time, the sunset provision would eliminate the entire DATA Act. So, after seven years of recipient reporting and new data standards, all of the new transparency provisions would have to be fought for all over again.

It is a bad idea to repeal a permanent law and replace it with a temporary law, especially when there is no reason to repeal FFATA outright. FFATA, as a law, is far from fatally flawed. As it is currently written, FFATA simply no longer goes far enough for today's transparency community. The DATA Act's recipient reporting and data standardization provisions are good, but the obvious solution is not to erase a perfectly good law. Instead, Congress should focus on amending FFATA with the positive provisions of the DATA Act and other language that will permanently improve federal spending transparency.